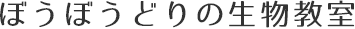

Twenty years ago, my colleague brought to my biology laboratory a cluster of strange-looking banana shaped egg sacs from the paddy fields. In those days, I did not really like walking in the mountains or paddy fields. I hated the bees and snakes in these places. Nor did I care much for the amphibians. However, as I observed those eggs incubating, something changed and I became interested in the small creatures inside. These eggs later hatched and from them came some kind of fish with external gills. They turned out to be what are called clouded salamanders. Two years later, I was able to have those salamanders lay unfertilized eggs in my laboratory and after that my chief interest became focused on how to fertilize salamander eggs in my laboratory. I have since succeeded in breeding numerous kinds of amphibians such as “Oita salamanders” and “Anderson’s alligator salamanders”.

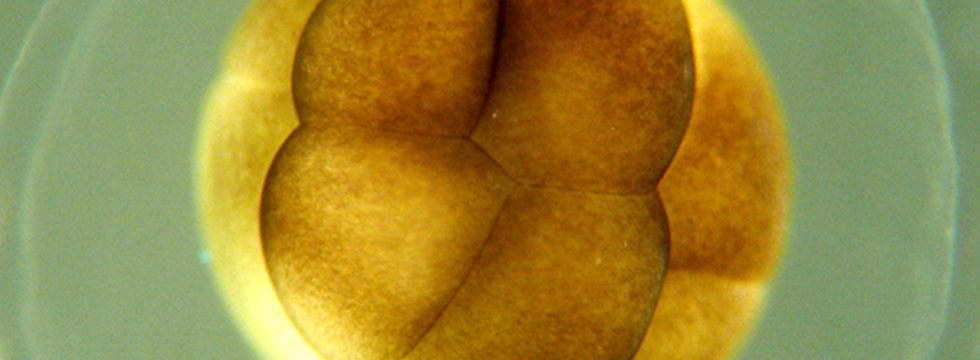

My laboratory, now filled with the various kinds of creatures I have bred, might well be called an amphibian zoo. My students visit my laboratory every day to feed the creatures and study their behavior. Doing outdoor research with my students has allowed me to witness first hand the destruction of amphibian habitats. This has encouraged me to start thinking about what things can be done to improve the current situation. I have also realized that there is a strong connection between what is happening in amphibian habitats and greater environmental issues.

Indeed, I myself have learned tremendously through keeping those small creatures. Through my experience teaching students about breeding amphibians, I better understand the educational value hands-on encounters with natural world. Simply put, in science, “knowledge” is not enough. We need “real experience”. We need to touch; to feel; to hear, smell and taste (Please do not eat the salamanders). I believe that such contact with nature is instrumental for cultivating student interest in science as well as nourishing a scientific way of thinking.

Seishin Girls’ High School AKIYAMA Shigeharu