1. Introduction

Twenty years ago, my colleague brought to my biology laboratory a cluster of strange-looking banana shaped egg sacs from the paddy fields. In those days, I did not really like walking in the mountains or paddy fields. I hated the bees and snakes in these places. Nor did I care much for the amphibians. However, as I observed those eggs incubating, something changed and I became interested in the small creatures inside. These eggs later hatched and from them came some kind of fish with external gills. They turned out to be what are called clouded salamanders. Two years later, I was able to have those salamanders lay unfertilized eggs in my laboratory and after that my chief interest became focused on how to fertilize salamander eggs in my laboratory. I have since succeeded in breeding numerous kinds of amphibians such as “Oita salamanders” and “Anderson’s alligator salamanders”.

My laboratory, now filled with the various kinds of creatures I have bred, might well be called an amphibian zoo. My students visit my laboratory every day to feed the creatures and study their behavior. Doing outdoor research with my students has allowed me to witness first hand the destruction of amphibian habitats. This has encouraged me to start thinking about what things can be done to improve the current situation. I have also realized that there is a strong connection between what is happening in amphibian habitats and greater environmental issues.

Indeed, I myself have learned tremendously through keeping those small creatures. Through my experience teaching students about breeding amphibians, I better understand the educational value hands-on encounters with natural world. Simply put, in science, “knowledge” is not enough. We need “real experience”. We need to touch; to feel; to hear, smell and taste (Please do not eat the salamanders). I believe that such contact with nature is instrumental for cultivating student interest in science as well as nourishing a scientific way of thinking.

2. Real-life Encounters with Creatures

Two primary objectives of science education at the elementary school level are cultivating a love of nature and developing the ability to solve problems. All elementary school students take the subject “Seikatsu-ka”, in which they experience taking care of animals. I decided to give my students the assignment of writing a research report on how their own elementary schools are taking care of their school pets and how they are using those pets for educational purposes. I have been giving this research assignment to my students annually since 1999. To my surprise, some students enclosed in their report a photo of a notice attached to the animal cages which read, “Keep away from this cage! Students responsible for feeding only!” I thought to myself, what is the point of keeping animals if nearly no one can interact with them? Not surprisingly, my students seem to be lacking in memories of seeing their school animals. I thus decided a few years ago to send out questionnaires to all the elementary schools in my prefecture, Okayama, in order to find out how they were taking care of their animals. This research revealed some eye-opening results.

Rabbits – cute and cuddly - are the most popular animals kept at schools here. However, 54 percent of the schools surveyed could not tell whether their rabbits were female or male. As a result, 65 percent were keeping males mixed with females and 91 percent were keeping their rabbits without using any kind of population control treatment. Some schools were keeping as many as 40 rabbits. Since the school teachers do not have the proper understanding of the animals’ behaviors, they are confronted by numerous difficulties. However, what surprised me most was that during the past ten years three students were denied entry when they tried to visit the elementary school from which they graduated. I do not know exactly the reason the students were prevented from seeing the animals, however the schools might be aware of some problems in their dealings with their pets.

The Governmental Educational Council feels keeping animals at schools helps deliver the Heart-Enriching education they wish to give students. At schools, however, numerous problems prevent this from happening: teachers’ lack of knowledge, insufficient financial support for keeping animals, and the burdens of keeping living creatures. These conditions, as well as the current issue of “Bird Flu” make many educators reluctant to keep animals at school.

So when asked the question: “What would make you sadder, the death of a pet at home or the death of a pet at school?, nearly all students reply “a pet at home.” The reason for this reaction simple: the more contact children have with an animal, the more attachment they will feel to it. So yes, rabbits can be good creatures to keep at school, so long as we limit their number to two or three and use suitable population control treatments. Using animals to enrich the hearts of students is good thinking, but the teachers need to be knowledgeable and the students must be able to have contact with the animals.

3. Female students’ lack of encounters with nature

Here in Japan, only a limited number of females are active in scientific fields. As a result of cultural norms and historical circumstance, our country has held a negative attitude toward women’s participation in prominent academic occupations. A white paper from the Ministry of Education showed that even elementary school students have strong ideas of gender roles. The paper pointed out that “all children are having fewer and fewer opportunities for contact with nature and the world beyond the home, the kind of experiences that are crucial for children’s further development.” Having less contact with nature might be one of the main causes for children’s – and especially women’s - decreased interest in science fields.

Seventh graders were asked, “Do you go catching insects?” 59.3 percent of boys interested in science answered “yes”, whereas only 35.9 percent of boys with no interest in science answered “yes”. The girls’ reactions were very different from those of boys. Only 35.9 percent of girls interested in science answered “yes, I go catching insects” whereas 27.7 percent of girls without interest in science answered “yes.”

The survey indicates that girls are likely to have much less contact with nature compared to boys, most likely due to biased views of gender roles. When students do experiments in class, girls are likely to assume assisting roles to boys, and not take on leading roles. The fact that only a limited number of girls take courses in science is, I believe, in part a result of their limited opportunities for experiencing nature. So, in order to increase the number of female scientists, we need to have programs that enable girls to experience nature first hand.

4. Building a program around contact with nature in the high school education curriculum.

Since my school is a girls’ high school, all the activities, such as Student Council activities as well as club activities, are carried out by female students. This also means that our school provides an ideal circumstance for training girls to positively take leadership in school activities. I therefore initiated the program for female students to cultivate their interest in scientific fields. I believe in the value of this because Japan has only a limited number of female scientists as compared with the rest of the world.

In 2006 we were designated by Ministry of Education as a Super Science High School and for the past four years, we have been building a unique school curriculum. We also established the “Life Science Course” in our school curriculum in which we provide students with numerous opportunities for field study. We focused on this because in Japan, the life science field is among the most popular areas for female scientists.

5. Content of our educational program for “Life Science Course”

The Life Science Course incorporates three core elements in order to give students hands-on experience in the natural world: ① Study Workshops which foster students interest in scientific fields; ② Experiments with university researchers; ③ Research assignments. All of these programs are being carried out with the gracious assistance of neighboring university researchers

① Study Workshops

Our program provides a 5-day Field Study Workshop for first year students, and a 4-day study workshop in Okinawa for second year students. A Study Workshop in Borneo is available for students of all grades, if they wish to participate.

At the Field Study Workshop, students learn about the forests and environmental issues from university lecturers and from hands-on research training. Activities include measuring and calculating the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by an assigned area of the forests.

At the Okinawa Study Workshop, students listen to research workers’ lectures concerning the behavior of local animals such as wildcats and bats. They also have a chance to observe the plants and animals in mangrove forests as well as sea life while snorkeling and kayaking.

At the Borneo Study Workshop, students attend Sabah University where they listen to lectures on plants and animals by resident professors. They also observe the plants and animals of Kinabalu Park(World Heritage) as well as the area along the Kinabatangan River. During this program, our students have the opportunity to interact with Malaysian high school students by giving presentations on their individual research in English.

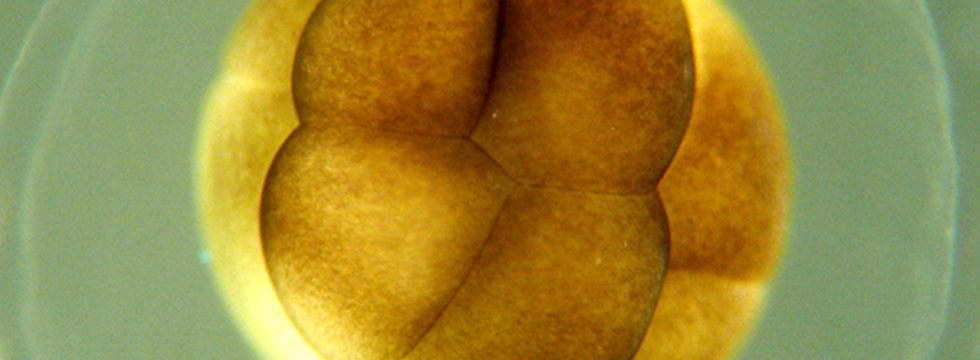

② Experiments at neighboring universities

In addition to ordinary classes, we visit our neighboring universities which allows our students to gain experience doing experiments with professional researchers. In the classes called “Life Science PracticeⅠ”and “Life Science PracticeⅡ”, our students learn applied life science at a level far beyond the that of high school science textbooks.

For “Life Science PracticeⅠ”we have formed a relationship with Fukuyama University. This relationship makes it possible for our students to get inside the university research laboratories. The students learn the fundamentals of the specialized areas of marine biotechnology and applied biological science.

For “Life Science PracticeⅡ, we have formed a relationship with the Okayama University of Science. There students are able to practice such things as DNA extraction.

③ Research Assignments

Students can choose the research topics from three different groups. I instruct the group of students whose interests are urodele amphibians and yeast.

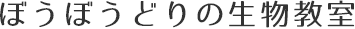

The aims of our research on the urodele amphibians are as follows: to establish the procedures of artificial fertilization, to raise the ratio of normal hatching, to prolong the capability of eggs and sperm to achieve fertilization, to find the proper density for keeping larvae, feeding them and preventing canibalism.

As for our research on yeast, we are tackling the issues of classifying yeast extracted from flowers and fruits As the yeasts inhabit the different kinds of flowers, analyzing the relations between the yeasts and the flowers may reveal something useful in understanding the ecosystem and related ecological issues. We classify the yeasts in accordance with the shapes observed under microscopes, the DNA arrangements, the electrophoretic karyotyping, and their fermentation capacities.

6. The program’s effects on our students

The SSH (Super Science High School) project offered us the opportunity to build an unprecedented program for female students. Focusing on providing practical “encounters” with nature, our curriculum forces our students to take positive leadership in their research activities, and to develop their presentation skills which are integral for communicating with an international audience. The other favorable effects on our students are shown in the charts below.

This year, our students are not planning to go out to distant areas for their research activities. We have chosen to stay in our local area and take a closer look at natural creatures around our school - our institution stands on a hill surrounded by trees and paddy fields.

Currently, observing the plants on the hill and the creatures inhabiting in paddy fields are among the students’ research assignments. Students are now eager to find out about the behaviors of the local Reeves’s pond turtles and Red-ear sliders. They will employ the “mark-and-recapture method” as well as “biotelemetry”. We would like to further continue providing education focusing on this kind of contact with animals and with nature.

I would like to finish with an interesting bit of information from a survey conducted by Dr. Hishoshi Nakano. In that survey one third of elementary school children answered yes when asked whether they thought dead people could live again. This was reported in newspaper articles, and critics suggested that something was desperately lacking in the education curriculum. What was lacking, many argued, was the ‘Heart-Enriching education’ which is to say the study of life and the living world. But without encountering that living world as it is, such heart-enriching education is simply not possible. I wonder if this is only true with elementary school children. What about junior high school students and high school students? What about college students, and moreover, even adults?

It is my firm belief that in our age, for all generations, real-life encounters with nature are indispensable to our education, and to live our lives as humans.

Shigeharu AKIYAMA, Seishin Girls' Upper Secondary School, Okayama

Society of Japan Science Teaching

SCIENCE EDUCATION MONTHLY

2009/Vol.58/No.689